BEEF producers were warned about the dangers of selecting for increasingly larger mature cow size, during a session at the 2022 Wagyu Edge Conference in Melbourne last week.

US animal scientist Dr Ken Olson from South Dakota State University, provided an account of how the US industry has changed over the past 20 odd years, plotting cow size increases, how this corresponds with US cow herd size, and how increased weight impacts on cow productivity.

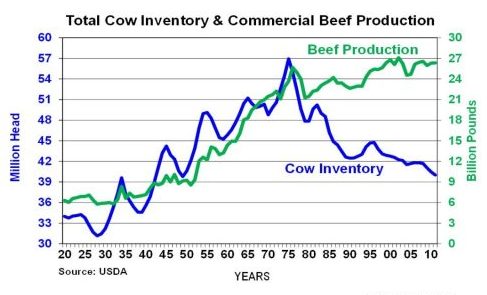

His first graph below (figure 1) shows how US beef production (green line) has continued to grow over the past century, while at the same time there has been a sharp decline in US breeding herd numbers since the mid-1970s, when it peaked at a population of about 45 million cows. Numbers were now on the verge of dropping below 30 million breeding cows ‘any day’.

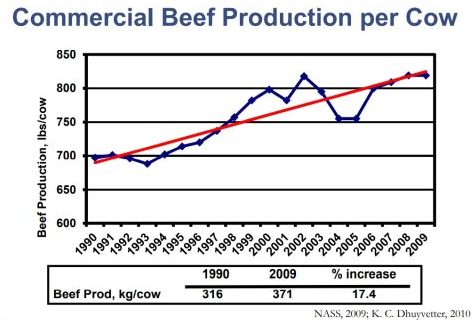

As this graph shows, beef production per US cow has continued to climb over the past 20-odd years, rising from 316kg/cow in 1990 to 371kg/cow by 2009 – a 17pc increase in 20 years.

“How did we do that?” Prof Olson asked. “We made bigger carcases, creating progeny that could grow faster and get bigger. But did that mean those cows that produced those calves also get bigger?”

He said back in the 1960s-70s, the typical US breeding cow weighed 450-500kg and was Hereford based. Starting in the 1980s, the industry got into crossbreeding in a big way, bringing in a lot of terminal European breeds with a lot more growth potential.

“But in our US industry, we did a pretty poor job of managing our crossbreeding systems, turning into what I called ‘Bull of the month club’. It was a progression of breeds, and it wasn’t well managed. It became a mess.”

The way commercial beef producers pulled back from that was to go back to straight-breeding, replacing Hereford with Angus, which now constituted the lion’s share of the US beef cattle herd.

“Angus is the breed the US industry has used to try to improve everything, and clean-up the mess we’d made,” he said.

So how fast did US Angus get bigger, and how big have they gotten?

Prof Olson used three sources of information to illustrate the changes seen in US cow size.

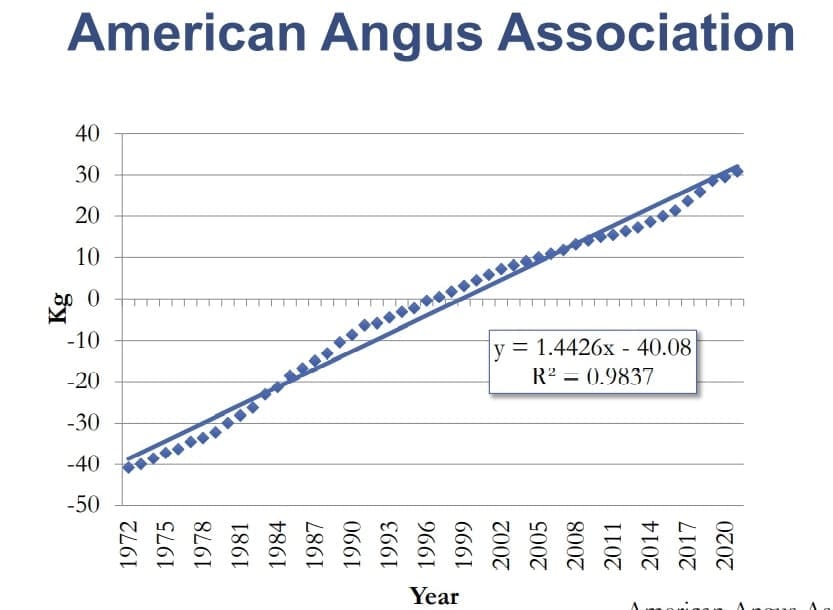

The first was genetic predictors (US EPDs, the equivalent of Australia’s EBVs). EPD values are half those seen in EBVs, because only half the genetics in an animal come from the cow. The figures were based on vast amounts of data generated by the American Angus Association.

Both EPDs for US mature cow weight and mature cow height had gotten much bigger. Since 1972, mature cow weights have grown steadily. In essence, cow size has gone up at the rate of 1.44kg per year, every year for the past 50 years.

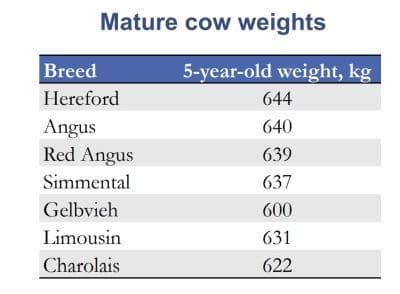

Another indicator was from the USDA ARS Germplasm evaluation program, comparing seven popular US breeds. It showed average US cow size by 2009 (environmental influences removed) was 630kg.

“There were differences in cow size among the breeds, but all had gotten bigger,” he said.

“Originally the European breeds that were brought into the US had heavier mature cow weights. But by 2009 data, the British breeds did not only catch up – they actually shot past the Euro and continental breeds.”

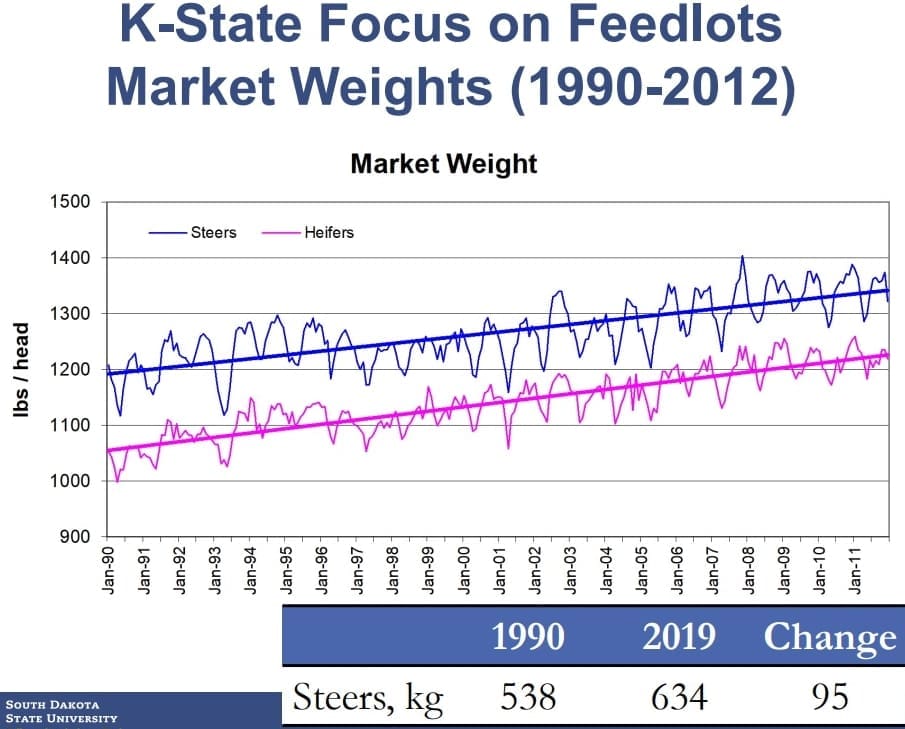

The third indicator of changes in US mature cow size came from simple logic. The common belief in the US for many years was that the finished weight of a steer calf would match his mother’s mature weight. Research had shown this to be true.

Prof Olson’s next graph, plotting US feedlot market-ready weights for ten million steers and heifers from Kansas feedlots slaughtered between 1990 and 2019 shows just how far US carcase weights (as a proxy for their mothers’ mature weights) have come. Fed steers, for example, have ballooned from 538kg average carcase weight to 634kg by 2019 – a rise of 95kg in 30 years. The trend for fed heifers (pink line) is similar.

So how do trends in the Australian beef industry compare?

There’s no shortage of evidence that a similar trend is occurring in Australia – although it is not yet anywhere near as extreme.

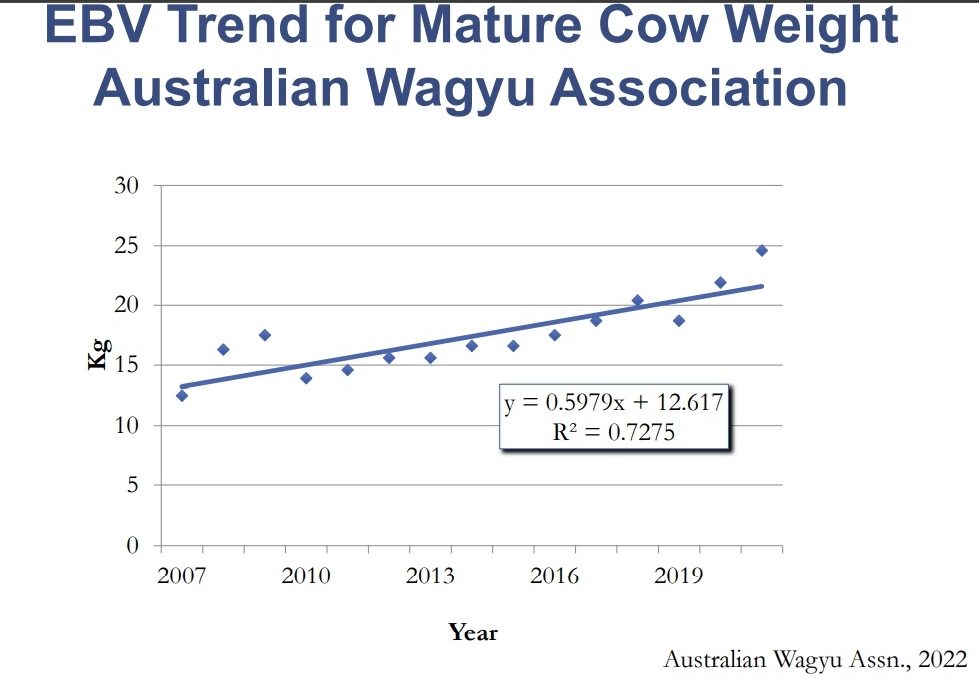

Prof Olson extracted ‘hot of the press’ EBV data for Wagyu cattle in Australia. It showed mature cow size since 2007 has grown in Wagyu cows, by about 12.6kg to 2021.

“You guys all have to decide, do I want my cows to get bigger?” he told the conference.

“Do I want to chase carcase weight so hard, that cows continue to get bigger, or do I want to find a way to increase carcase weight, while uncoupling the genetic relationship between progeny carcase weight and mature cow weight?

“It can be uncoupled. It’s not easy, because the two are strongly related, but at least in the US, there are some beef sires that can be used that can help slow down the increase in cow size, while continuing to increase carcase size.”

He said the average rate of gain in Wagyu cows in Australia, according to the EBV data was still only 0.6kg per year, compared with the earlier US Angus data, where the increase is 1.44kg/year.

“What this says is that you folks (Australian Wagyu breeders) have cows that are getting bigger as the years go by, but currently at a much slower rate than in US cattle.”

“From what I have observed since arriving in Australia, that’s probably because you guys are much more focussed on what your breed is famous for – marbling scores, and the eatability of the product, than you are on maximising the kilos of carcase weight per beast.

“But the trend is there. You are going to have to consider this data and what it means for the way you manage the genetics in the Australian Wagyu cow herd. I’m here to tell you what’s possible, and what happens if you don’t limit it.”

Management standpoint

Prof Olsen also applied some of the mature cow weight numbers to what it means, from a herd management standpoint.

“If my (grazing) resources are unlimited, there’s probably little reason to care about bigger carcases. But the problem is, as they get bigger, their nutrient requirements go up.

“Luckily, it’s not in direct proportion to the rate of weight increase – it is in proportion with surface area of the animal – and the energy they need to consume every day. So it’s about volume, rather than weight.”

“That works in our favour, because as the surface area of an animal (all animals, not just cows) goes up, its surface area goes up at a slower rate than weight.

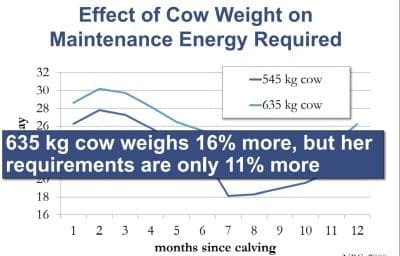

Using the graph below, Prof Olson illustrated this by pointing out that a 635kg cow has an 11pc higher maintenance energy requirement than a 545kg cow, that was 16pc lighter in weight.

“There is an advantage in letting your cows get bigger, simply in maintenance cost in that cow keeping herself alive. But to do that, the heavier cow needs to eat more. The heavier cow requires 478kg extra feed, dry matter basis over a year, to cover the 11pc difference in nutrient requirement.

“There is an advantage in letting your cows get bigger, simply in maintenance cost in that cow keeping herself alive. But to do that, the heavier cow needs to eat more. The heavier cow requires 478kg extra feed, dry matter basis over a year, to cover the 11pc difference in nutrient requirement.

“You may have to feed that cow nearly 500kg more forage, or you might have to supplementary feed, to fill that gap – but one way or another, for that cow to meet her lifetime requirements and still get pregnant and carry that pregnancy to term and milk while that calf is at her side, and re-breed – she is going to need to eat more.”

So how much more does a bigger cow have to produce to cover her higher feed bill?

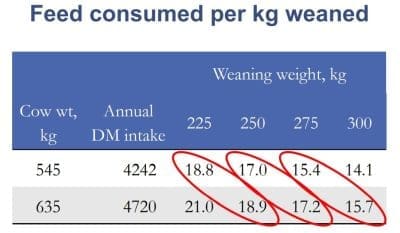

The graph below, based on weaning weights typical in South Dakota, shows the 635kg cow needs 25kg more weaning weight to match the feed efficiency of a 545kg cow.

Is this likely? The US Angus EPD database suggested it was not, Prof Olsen said, as weaning weights had lagged behind cow size, adding only 15kg of weight over the past 20 years. All of the additional carcase growth happening in the US industry was happening post-weaning.

He said for a given grazing property adding 90kg of cow weight to every cow on the place, it was important to ask: Do you have the forage resources on the place to meet those cows’ needs?

“In general, as cow weight increases or as they increase milk production, nutrient requirement increases. Grazing resources vary tremendously across the US, just as they do in Australia.”

“Extreme sizes rarely fit. You don’t ever want to have the very largest cows in the world, nor the smallest. Somewhere in the middle, you have to shift where your cow herd is, relative to the available forage resources.

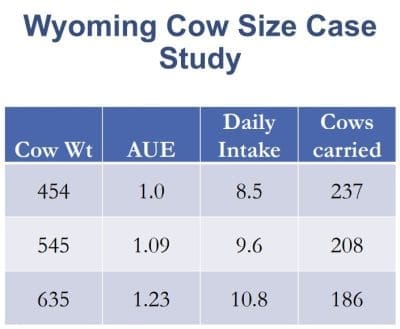

A study in Wyoming looking at how cow sized mattered in the grazing environment, in three cow mobs divided by weight, was measured for animal unit equivalents. Based on daily dry matter intake, the lightest group of cows averaging 445kg could run 237 head on the given area, while the heaviest averaging 635kg could accommodate a stocking rate of only 186 head.

“But how many ranches in the US have reduced their breeding herd populations over the past 20 years, as their cows sizes have increased?” Prof Olsen asked.

“The answer is none. They can’t afford to. So what do they do to make up for that? They either let a lot of cows fail, measured as pregnancy rates, or they start bringing in a lot more supplementary feed.”

“And that’s what’s happening in the US.”

First published – 05 May 2022 by BeefCentral